This is how the ancient people called the island, which was a pan-hellenic cult centre like the island of Delos.

An island in the Aegean Sea near the Thracian coast opposite the mouth of the Evros river. Homer calls it Samothrace (Il. 13.12) and Samos (Il. 24.78 & 753).

According to Apollodorus, he was the son of Electra by Zeus and brother of Dardanus (Apollod. 3,12,1), who loved Demeter but was slain by Zeus with a thunderbolt (Od. 5.125).

Iasion or Iasius (Iasion or Iasios). Son of Zeus and Electra, beloved by Demeter,

who, in a thrice-ploughed field (tripolos), became by him the mother

of Pluto or Plutus in Crete. He was slain by Zeus with a thunderbolt. From Iasion

came the patronymic Iasides, a name given to Palinurus, as a descendant of Atlas.

Iasion, also called Iasius, was, according to some, a son of Zeus and Electra, the daughter of Atlas, and a brother of Dardanus (Apollod. iii. 12.1; Serv. ad Aen. i. 384; Hes. Theog. 970; Ov. Amor. iii. 10, 25); but others called him a son of Corythus and Electra, of Zeus and the nymph Hemera, or of Ilithyius, or of Minos and the nymph Pyronia (Schol. ad Theocrit. iii. 30; Serv. ad Aen. iii. 167; Eustath. ad Hom; Hygin. Fab. 270). At the wedding of his sister Harmonia, Demeter fell in love with him, and in a thrice-ploughed field (tripolos) she became by him the mother of Pluton or Plutus in Crete, in consequence of which Zeus killed him with a flash of lightning (Hom. Od. v. 125, &c.; Hes. Theog. 969, &c.; Apollod. l. c.; Diod. v. 49, 77; Tzetz. ad Lycoph. 29; Conon, Narrat. 21). According to Servius (ad Aen. iii. 167), Iasion was slain by Dardanus, and according to Hyginus (Fab. 250) he was killed by his own horses, whereas others represent him as living to an advanced age as the husband of Demeter (Ov. Met. ix. 421, &c.). In some traditions Eetion is mentioned as the only brother of Dardanus (Schol. ad Apollon. Rhod. i. 916; Tzetz. ad Lycoph. 219), whence some critics have inferred that Iasion and Eetion are only two names for the same person. A further tradition states that Iasion and Dardanus, being driven from their home by a flood, went from Italy, Crete, or Arcadia, to Samothrace, whither he carried the Palladium, and where Zeus himself instructed him in the mysteries of Demeter (Serv. ad Aen. iii. 15, 167, vii. 207; Dionys. i. 61; Diod. v. 48; Strab. vii.; Conon, l. c.; Steph. Byz. s. v. Dardanos). According to Eustathius (ad Hom.), Iasion, being inspired by Demeter and Cora, travelled about in Sicily and many other countries, and every where taught the people the mysteries of Demeter.

This text is from: A dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology, 1873 (ed. William Smith). Cited Jan 2006 from The Perseus Project URL below, which contains interesting hyperlinks

Cabeiri (Kabeiroi), mystic divinities who occur in various parts of the ancient

world. The obscurity that hangs over them, and the contradictions respecting them

in the accounts of the ancients themselves, have opened a wide field for speculation

to modern writers on mythology, each of whom has been tempted to propound a theory

of his own. The meaning of the name Cabeiri is quite uncertain, and has been traced

to nearly all the languages of the East, and even to those of the North; but one

etymology seems as plausible as another, and etymology in this instance is a real

ignis fatuus to the inquirer. The character and nature of the Cabeiri are as obscure

as the meaning of their name. All that we can attempt to do here is to trace and

explain the various opinions of the ancients themselves, as they are presented

to us in chronological succession. We chiefly follow Lobeck, who has collected

all the passages of the ancients upon this subject, and who appears to us the

most sober among those who have written upon it.

The earliest mention of the Cabeiri, so far as we know, was in a drama

of Aeschylus, entitled Kabeiroi, in which the poet brought them into contact with

the Argonauts in Lemnos. The Cabeiri promised the Argonauts plenty of Lemnian

wine (Plut. Sympos. ii. 1; Pollux, vi. 23). The opinion of Welcker, who infers

from Dionysius (i. 68, &c.) that the Cabeiri had been spoken of by Arctinus, has

been satisfactorily refuted by Lobeck and others. From the passage of Aeschylus

here alluded to, it appears that he regarded the Cabeiri as original Lemnian divinities,

who had power over everything that contributed to the good of the inhabitants,

and especially over the vineyards. The fruits of the field, too, seem to have

been under their protection, for the Pelasgians once in a time of scarcity made

vows to Zeus, Apollo, and the Cabeiri (Myrsilus, ap. Dionys. i. 23). Strabo in

his discussion about the Curetes, Dactyls, &c., speaks of the origin of the Cabeiri,

deriving his statements from ancient authorities, and from him we learn, that

Acusilaus called Camillus a son of Cabeiro and Hephaestus, and that he made the

three Cabeiri the sons, and the Cabeirian nymphs the daughters, of Camillus. According

to Pherecydes, Apollo and Rhytia were the parents of the nine Corybantes who dwelled

in Samothrace, and the three Cabeiri and the three Cabeirian nymphs were the children

of Cabeira, the daughter of Proteus, by Hephaestus. Sacrifices were offered to

the Corybantes as well as the Cabeiri in Lemnos and Imbros, and also in the towns

of Troas. The Greek logographers, and perhaps Aeschylus too, thus considered the

Cabeiri as the grandchildren of Proteus and as the sons of Hephaestus, and consequently

as inferior in dignity to the great gods on account of their origin. Their inferiority

is also implied in their jocose conversation with the Argonauts, and their being

repeatedly mentioned along with the Curetes, Dactyls, Corybantes, and other beings

of inferior rank. Herodotus (iii. 37) says, that the Cabeiri were worshipped at

Memphis as the sons of Hephaestus, and that they resembled the Phoenician dwarf-gods

(Pataikoi) whom the Phoenicians fixed on the prows of their ships. As the Dioscuri

were then yet unknown to the Egyptians (Herod. ii. 51), the Cabeiri cannot have

been identified with them at that time. Herodotus proceeds to say, "the Athenians

received their phallic Hermae from the Pelasgians, and those who are initiated

in the mysteries of the Cabeiri will understand what I am saying; for the Pelasgians

formerly inhabited Samothrace, and it is from them that the Samothracians received

their orgies. But the Samothracians had a sacred legend about Hermes, which is

explained in their mysteries". This sacred legend is perhaps no other than the

one spoken of by Cicero (De Nat. Deor. iii. 22), that Hermes was the son of Coelus

and Dies, and that Proserpine desired to embrace him. The same is perhaps alluded

to by Propertius (ii. 2. 11), when he says, that Mercury (Hermes) had connexions

with Brimo, who is probably the goddess of Pherae worshipped at Athens, Sicyon,

and Argos, whom some identified with Proserpine (Persephone), and others with

Hecate or Artemis. We generally find this goddess worshipped in places which had

the worship of the Cabeiri, and a Lemnian Artemis is mentioned by Galen. The Tyrrhenians,

too, are said to have taken away the statue of Artemis at Brauron, and to have

carried it to Lemnos. Aristophanes, in his " Lemnian Women," had mentioned Bendis

along with the Brauronian Artemis and the great goddess, and Nonnus (Dionys. xxx.

45) states that the Cabeirus Alcon brandished Hekates Diasodea purson, so that

we may draw the conclusion, that the Samothracians and Lemnians worshipped a goddess

akin to Hecate, Artemis, Bendis, or Persephone, who had some sexual connexion

with Hermes, which revelation was made in the mysteries of Samothrace.

The writer next to Herodotus, who speaks about the Cabeiri, and whose

statements we possess in Strabo, though brief and obscure, is Stesimbrotus. The

meaning of the passage in Strabo is, according to Lobeck, as follows: Some persons

think that the Corybantes are the sons of Cronos, others that they are the sons

of Zeus and Calliope, that they (the Corybantes) went to Samothrace and were the

same as the beings who were there called Cabeiri. But as the doings of the Corybantes

are generally known, whereas nothing is known of the Samothracian Corybantes,

those persons are obliged to have recourse to saying, that the doings of the latter

Corybantes are kept secret or are mystic. This opinion, however, is contested

by Demetrius, who states, that nothing was revealed in the mysteries either of

the deeds of the Cabeiri or of their having accompanied Rhea or of their having

brought up Zeus and Dionysus. Demetrius also mentions the opinion of Stesimbrotus,

that the hiera were performed in Samothrace to the Cabeiri, who derived their

name from mount Cabeirus in Berecyntia. But here again opinions differed very

much, for while some believed that the hiera Kabeiron were thus called from their

having been instituted and conducted by the Cabeiri, others thought that they

were celebrated in honour of the Cabeiri, and that the Cabeiri belonged to the

great gods.

The Attic writers of this period offer nothing of importance concerning

the Cabeiri, but they intimate that their mysteries were particularly calculated

to protect the lives of the initiated (Aristoph. Pax, 298). Later writers in making

the same remark do not mention the name Cabeiri, but speak of the Samothracian

gods generally (Diod. iv. 43, 49; Aelian, Fragm.; Callim. Ep. 36; Lucian. Ep.

15; Plut. Marcell. 30). There are several instances mentioned of lovers swearing

by the Cabeiri in promising fidelity to one another (Juv. iii. 144; Himerius,

Orat. i. 12); and Suidas (s. v. Dialamdanei) mentions a case of a girl invoking

the Cabeiri as her avengers against a lover who had broken his oath. But from

these oaths we can no more draw any inference as to the real character of the

Cabeiri, than from the fact of their protecting the lives of the initiated; for

these are features which they have in common with various other divinities. From

the account which the scholiast of Apollonius Rhodius (i. 913) has borrowed from

Athenion, who had written a comedy called The Samothracians (Athen. xiv.), we

learn only that he spoke of two Cabeiri, Dardanus, and Jasion, whom he called

sons of Zeus and Electra. They derived their name from mount Cabeirus in Phrygia,

from whence they had been introduced into Samothrace.

A more ample source of information respecting the Cabeiri is opened

to us in the writers of the Alexandrine period. The two scholia on Apollonius

Rhodius contain in substance the following statement: Mnaseas mentions the names

of three Cabeiri in Samothrace, viz. Axieros, Axiocersa, and Axiocersus; the first

is Demeter, the second Persephone, and the third Hades. Others add a fourth, Cadmilus,

who according to Dionysius that dorus is identical with Hermes. It thus appears

these accounts agreed with that of Stesimbrotus, who reckoned the Cabeiri among

the great gods, and that Mnaseas only added their names. Herodotus, as we have

seen, had already connected Hermes with Persephone; the worship of the latter

as connected with that of Demeter in Samothrace is attested by Artemidorus (ap.

Strab. iv.); and there was also a port in Samothrace which derived its name, Demetrium,

from Demeter (Liv. xlv. 6). According to the authors used by Dionysius (i. 68),

the worship of Samothrace was introduced there from Arcadia; for according to

them Dardanus, together with his brother Jasion or Jasus and his sister Harmonia,

left Arcadia and went to Samothrace, taking with them the Palever, ladium from

the temple of Pallas. Cadmus, however, who appears in this tradition, is king

of Samothrace: he made Dardanus his friend, and sent him to Teucer in Troas. Dardanus

himself, again, is sometimes described as a Cretan (Serv. ad Aen. iii. 167), sometimes

as an Asiatic (Steph. s. v. Dardanos; Eustath. ad Dionys. Perieg. 391), while

Arrian (ap. Eustath.) makes him come originally from Samothrace. Respecting Dardanus'

brother Jasion or Jasus, the accounts likewise differ very much; for while some

writers describe him as going to Samothrace either from Parrhasia in Arcadia or

from Crete, a third account (Dionys. i. 61) stated, that he was killed by lightning

for having entertained improper desires for Demeter; and Arrian says that Jasion,

being inspired by Demeter and Cora, went to Sicily and many other places, and

there established the mysteries of these goddesses, for which Demeter rewarded

him by yielding to his embraces, and became the mother of Parius, the founder

of Paros.

All writers of this class appear to consider Dardanus as the founder

of the Samothracian mysteries, and the mysteries themselves as solemnized in honour

of Demeter. Another set of authorities, on the other hand, regards them as belonging

to Rhea (Diod. v. 51; Schol. ad Aristid.; Strab. Esccrpt. lib. vii.; Lucian, Dc

Dea Syr. 97), and suggests the identity of the Samothracian and Phrygian mysteries.

Pherecydes too, who placed the Corybantes, the companions of the great mother

of the gods, in Samothrace, and Stesimbrotus who derived the Cabeiri from mount

Cabeirus in Phrygia, and all those writers who describe Dardanus as the founder

of the Samothracian mysteries, naturally ascribed the Samothracian mysteries to

Rhea. To Demeter, on the other hand, they were ascribed by Mnaseas, Artemidorus,

and even by Herodotus, since he mentions Hermes and Persephone in connexion with

these mysteries, and Persephone has nothing to do with Rhea. Now, as Demeter and

Rhea have many attributes in common -both are megaloi Deoi- and the festivals

of each were celebrated with the same kind of enthusiasm; and as peculiar features

of the one are occasionally transferred to the other (e. g. Eurip. Helen. 1304),

it is not difficult to see how it might happen, that the Samothracian goddess

was sometimes called Demeter and sometimes Rhea. The difficulty is, however, increased

by the fact of Venus (Aphrodite) too being worshipped in Samothrace (Plin. H.

N. v. 6). This Venus may be either the Thracian Bendis or Cybele, or may have

been one of the Cabeiri themselves, for we know that Thebes possessed three ancient

statues of Aphrodite, which Harmonia had taken from the ships of Cadmus, and which

may have been the Pataaikoi who resembled the Cabeiri (Paus. ix. 16.2; Herod.

iii. 37). In connexion with this Aphrodite we may mention that, according to some

accounts, the Phoenician Aphrodite (Astarte) had commonly the epithet chabar or

chabor, an Arabic word which signifies "the great," and that Lobeck considers

Astarte as identical with the Selene Kabeiria, which name P. Ligorius saw on a

gem.

There are also writers who transfer all that is said about the Samothracian

gods to the Dioscuri, who were indeed different from the Cabeiri of Acusilaus,

Pherecydes, and Aeschylus, but yet might easily be confounded with them; first,

because the Dioscuri are also called great gods, and secondly, because they were

also regarded as the protectors of persons in danger either by land or water.

Hence we find that in some places where the anakes were worshipped, it was uncertain

whether they were the Dioscuri or the Cabeiri (Paus. x. 38.3). Nay, even the Roman

Penates were sometimes considered as identical with the Dioscuri and Cabeiri (Dionys.

i. 67, &c.); and Varro thought that the Penates were carried by Dardanus from

the Arcadian town Pheneos to Samothrace, and that Aeneas brought them from thence

to Italy (Macrob. Sat. iii. 4; Serv. ad Aen. i. 378, iii. 148). But the authorities

for this opinion are all of a late period. According to one set of accounts, the

Samothracian gods were two male divinities of the same age, which applies to Zeus

and Dionysus, or Dardanus and Jasion, but not to Demeter, Rhea, or Persephone.

When people, in the course of time, had become accustomed to regard the Penates

and Cabeiri as identical, and yet did not know exactly the name of each separate

divinity comprised under those common names, some divinities are mentioned among

the Penates who belonged to the Cabeiri, and vice versa. Thus Servius (ad Aen.

viii. 619) represents Zeus, Pallas, and Hermes as introduced from Samothrace;

and, in another passage (ad Aen. iii. 264), he says that, according to the Samothracians,

these three were the great gods, of whom Hermes, and perhaps Zeus also, might

be reckoned among the Cabeiri. Varro (de Ling. Lat. v. 58) says, that Heaven and

Earth were the great Samothracian gods; while in another place (ap. August. De

Civ. Dei, vii. 18) he stated, that there were three Samothracian gods, Jupiter

or Heaven, Juno or Earth, and Minerva or the prototype of things -the ideas of

Plato. This is, of course, only the view Varro himself took, and not a tradition.

If we now look back upon the various statements we have gathered,

for the purpose of arriving at some definite conclusion, it is manifest, that

the earliest writers regard the Cabeiri as descended from inferior divinities,

Proteus and Hephaestus: they have their seats on earth, in Samothrace, Lemnos,

and Imbros. Those early writers cannot possibly have conceived them to be Demeter,

Persephone or Rhea. It is true those early authorities are not numerous in comparison

with the later ones; but Demetrius, who wrote on the subject, may have had more

and very good ones, since it is with reference to him that Strabo repeats the

assertion, that the Cabeiri, like the Corybantes and Curetes, were only ministers

of the great gods. We may therefore suppose, that the Samothracian Cabeiri were

originally such inferior beings; and as the notion of the Cabeiri was from the

first not fixed and distinct, it became less so in later times; and as the ideas

of mystery and Demeter came to be looked upon as inseparable, it cannot occasion

surprise that the mysteries, which were next in importance to those of Eleusis,

the most celebrated in antiquity, were at length completely transferred to this

goddess. The opinion that the Samothracian gods were the same as the Roman Penates,

seems to have arisen with those writers who endeavoured to trace every ancient

Roman institution to Troy, and thence to Samothrace.

The places where the worship of the Cabeiri occurs, are chiefly Samothrace,

Lemnos, and Imbros. Some writers have maintained, that the Samothracian and Lemnian

Cabeiri were distinct; but the contrary is asserted by Strabo. Besides the Cabeiri

of these three islands, we read of Boeotian Cabeiri. Near the Neitian gate of

Thebes there was a grove of Demeter Cabeiria and Cora, which none but the initiated

were allowed to enter; and at a distance of seven stadia from it there was a sanctuary

of the Cabeiri (Paus. ix. 25.5). Here mysteries were celebrated, and the sanctity

of the temple was great as late as the time of Pausanias (Comp. iv. 1.5). The

account of Pausanias about the origin of the Boeotian Cabeiri savours of rationalism,

and is, as Lobeck justly remarks, a mere fiction. It must further not be supposed

that there existed any connexion between the Samothracian Cadmilus or Cadmus and

the Theban Cadmus; for tradition clearly describes them as beings of different

origin, race and dignity. Pausanias (ix. 22.5) further mentions another sanctuary

of the Cabeiri, with a grove, in the Boeotian town of Anthedon; and a Boeotian

Cabeirus, who possessed the power of averting dangers and increasing man's prosperity,

is mentioned in an epigram of Diodorus. A Macedonian Cabeirus occurs in Lactantius.

The reverence paid by the Macedonians to the Cabeiri may be inferred from the

fact of Philip and Olympias being initiated in the Samothracian mysteries, and

of Alexander erecting altars to the Cabeiri at the close of his Eastern expedition

(Plut. Alex. 2; Philostr. de Vit. Apollon. ii. 43). The Pergamenian Cabeiri are

mentioned by Pausanias (i. 4.6), and those of Berytus by Sanchoniathon and Damascius.

Respecting the mysteries of the Cabeiri in general, see Dict. of Ant. s. v. Cabeiria.

This text is from: A dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology, 1873 (ed. William Smith). Cited Sep 2005 from The Perseus Project URL below, which contains interesting hyperlinks

Legendary people of Boeotia, expelled by Argives, mysteries of C. instituted at Thebes by Methapus, sanctuary, history of rites, wrath of C. implacable, identified with Boy Lords at Amphissa, land of Pergamus sacred to, minor deities worshipped in many places, in Samothrace and Memphis.

Eurymedon. A Cabeirus, a son of Hephaestus and Cabeiro, and a brother of Alcon. (Nonn. Dionys. xiv. 22; Cic. de Nat. Deor. iii. 21.)

Axieros, a daughter of Cadmilus, and one of the three Samothracian Cabeiri. According to the Paris-Scholia on Apollonius (i. 915-921), she was the same as Demeter. The two other Cabeiri were Axiocersa (Persephone), and Axiocersus (Hades).

Son of Zeus and Electra, leaves Samothrace, marries the daughter of King Teucer, and calls the country Dardania, father of Idaea, receives image of Dionysus in chest from Zeus.

Perseus Project

According to the myth of the caclysm of Samothrace, only the Cabiri were saved.

The fame of the cult of the Mysteries at Samothrace was surpassed only by that at Eleusis

Cabeiria (ta kabeiria). The mysterious rites of the Pelasgic gods known as the

Cabeiri, celebrated in the islands lying between Euboea and the Hellespont, in

Lemnos, Imbros, and especially in Samothrace. This worship was also known on the

adjacent coasts of Europe and Asia Minor, at Thebes and Andania in Greece, and,

according to Strabo (iv.), in an island near Britannia. Like the Elensinia, an

almost complete secrecy had been maintained as to the ceremonies and teaching

of these mysteries. Yet we know the names of the gods; and, from an examination

of the various forms under which we find them, Lenormant has been able to discover

what he calls a Cabeiric group. They are four in number, thus differing essentially

from the Phoenician Kabirim, who, as their Semitic name shows, are also "great

gods", but are eight in number, representing the planets and the universe

formed from their union. The names of the Samothracian Cabeiri, as revealed by

Mnaseas of Patara and Dionysodorus, two historians of the Alexandrian Age, are

Axieros (=Demeter), Axiokersa (=Persephone), Axiokersos (=Hades), Casmilos (=Hermes).

Sometimes the two goddesses blend in one, viz. Earth (Varro, L. L. v. 58); sometimes

as Aphrodite and Venus; but to most of the Romans they represent Juno and Minerva

( Serv. ad Verg. Aen.iii. 12). Axiokersos appears further as Zeus, Uranus, Iupiter,

Apollo, Dionysus-Liber; and Casmilos as Mercurius or Eros. The group is a primal

mother goddess, whose issue are two divinities, a male and a female, from whom

again springs a fourth, Casmilos, the orderer of the universe.

Herodotus (ii. 51) is the first historian who mentions them. Though

known while Athens was flourishing (Aristoph. Pax, 277), it was not till Alexandrian

times that they really became famous. During this period Samothrace was a sort

of sacred island, as it was under the Roman dominion, for the idea was prevalent

that the Penates (Serv. ad Verg. Aen.ii. 325 Verg. Aen., iii. 12Verg. Aen., viii.

619) were identical with the gods of Samothrace. Legend told how that Dardanus,

Eetion, or Iasion, and Harmonia, wife of Cadmus, were children of Electra and

Zeus; that Iasion was given the mysteries by Zeus, married Cybele, and begat Corybas;

and after Iasion was received among the gods, Dardanus, Cybele, and Corybas brought

the mysteries to Asia. The legends vary in details, but almost all agree in making

Dardanus and Iasion sons of Zeus and Electra, and connecting the Samothracian

mysteries with them. It is to be remarked, in passing, that, while legend brought

the mysteries from Samothrace to Asia, there can be hardly any doubt that the

passage was the other way (cf. Strabo, x. 472); for the whole tenor of the worship

is Asiatic. We have many inscriptions of Romans who were initiated (C. I. L. iii.

713-721), and we hear besides of other Romans of high position who were initiated,

among them probably Cicero (Nat. Deor. i. 42, 119). Throughout the Roman period

the Cabeiric mysteries were held in high estimation, second only to the Eleusinian,

and they were still in existence in the time of Libanius.

From the earliest times, the Pelasgi are said to have sacrificed a

tenth of their produce to the Cabeiri in order to be preserved from famine. The

chief priest was probably the hierophantes mentioned by Galen (iii. 576); and

the purifying priest koes or koies. The basileus of the inscriptions was the highest

eponymous magistrate of Samothrace. As in all mysteries, the votary must be purified

in body and mind before initiation; and thus we have some evidence of auricular

confession. But, as far as we know, there was not any special preparatory intellectual

training required. Women and children appear to have been admitted as well as

men. Of the religious ceremonies themselves we may say we know nothing. They consisted

of dromena kai legomena. We hear of dances by the pii Samothraces, and the priests

who executed these dances were called Saoi (?). The Romans, who traced their Penates

to Samothrace, referred their Salii to these Saoi. There were two classes of votaries--

the mustai and the mustai eusebeis, mystae pii--the latter being apparently those

initiated for the first time. In the Samothracian mysteries, sacra accipere (paralambanein

ta musteria), which is the regular phrase for primary initiation, seems to be

applied to the higher grades. But the whole matter is quite obscure and unsettled.

The scholiast on Apollonius Rhodius tells us that the initiated wore

a purple band (tainia) round their waist (which reminds us of the Brahminical

thread); that Agamemnon quelled a mutiny of the Greeks by wearing one; and that

Odysseus, who wore a fillet for the band, was miraculously saved in shipwreck.

Preservation in times of peril, and especially in perils on the sea, was the chief

service that the Cabeiri were supposed to render to those who called on them by

name, and none knew their names except the initiated. It was the electric fires

of the Cabeiri that, according to the legend, lighted on the heads of the Dioscuri

during the Argonautic voyage. Diodorus further says, in the course of an important

discussion on the Cabeiri (v. 47-49), that those who were initiated became more

pious, more righteous, and in every respect better than they were before. On the

basis of this, Lenormant thinks it probable that the doctrine of rewards and punishments

in a future life was inculcated, though, with Lobeck, we may well suppose that

no more is necessarily implied than the impulse to virtue, which is always united

with religious emotion excited by impressive and gracious ceremonies (Cf. Apoll.

Rhod. i. 917).

The initiations at Samothrace took place at any time from May to September,

in this differing from the Eleusinian and more resembling the Orphic Mysteries.

There appears, however, to have been a specially great ceremony at the commencement

of August ( Lucull. 13).

From the manner in which Cicero speaks of the Samothracian mysteries

in the passage already cited, it is probable that he was initiated. He says of

their ceremonies, quibus explicatis ad rationemque revocatis, rerum magis natura

cognoscitur quam deorum. And the Cabeiri themselves do appear to be symbols of

the creation of the world. From the primeval mother emanate or differentiate themselves

two elements--matter (earth) and force (especially fire, celestial and terrestrial).

Indeed, the name Cabeiri appears to mean "the Burners", from kaiein,

and by the action of the former on the latter the ordered world is generated.

The etymological identity of the Pelasgian with the Phoenician Cabeiri is doubted

by Lenormant; the name of the latter being from a Semitic root, which in Arabic

appears as kebir, "great". Many hold that all the ceremonies of the

Cabeiri, and those of the other mysteries, were pure inventions of the priests,

nothing more than mere stories about gods. The reader, with regard to this phase

of the subject, is referred to the article Mysteria.

This text is from: Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities. Cited Sep 2005 from The Perseus Project URL below, which contains interesting hyperlinks

An island south of Thrace, formerly called Dardania, its Pelasgian inhabitants, exploit of a Samothracian ship at Salamis, Samothracian forts on the mainland, Dardanus leaves.

The Ephesians under Androclus made war on Leogorus, the son of Procles, who reigned in Samos after his father, and after conquering them in a battle drove the Samians out of their island, accusing them of conspiring with the Carians against the Ionians. The Samians fled and some of them made their home in an island near Thrace, and as a result of their settling there the name of the island was changed from Dardania to Samothrace.

The Samians fled and some of them made their home in an island near Thrace, and as a result of their settling there the name of the island was changed from Dardania to Samothrace.

After having plundered and destroyed the island, they slaughtered hundreds of inhabitants (who were almost 4.000) and they sold others as slaves.

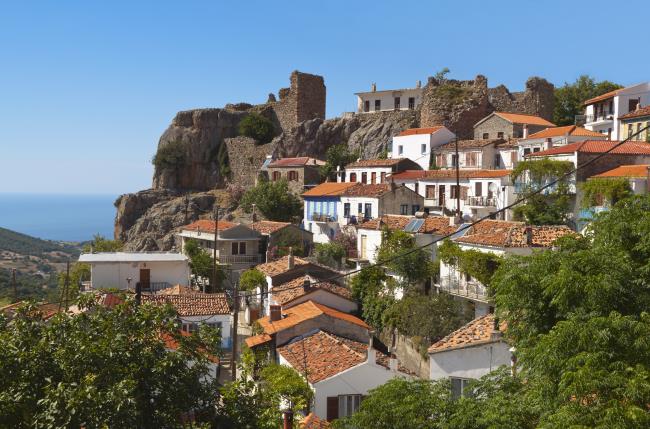

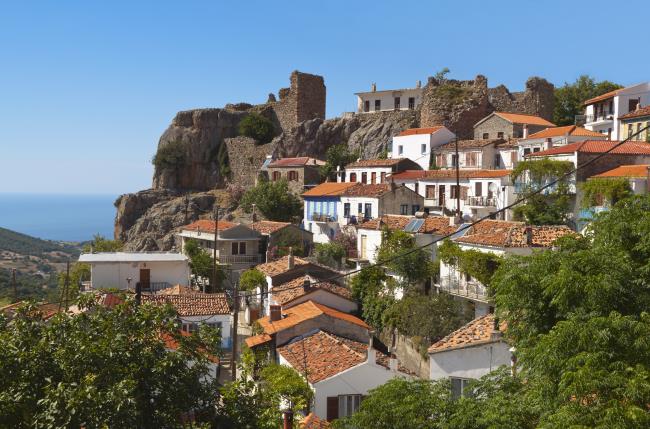

A mountainous island in the NE Aegean famous in antiquity for its

Sanctuary of the Great Gods. Sporadic finds indicate that it was inhabited in

the Neolithic Age, and pottery dating from the Bronze Age has been found at Kariotes

to the E of the later Greek city. The island was settled ca. 700 B.C. by Greek-speaking

colonists whose Aeolic dialect suggests that they came from NW Anatolia or Lesbos.

They mingled with the local population, whose Thracian tongue is documented as

the ritual language of the cult as late as the Augustan age. The archaic city,

as yet little explored, was protected by an impressive city wall. A naval power

owning territory on the Thracian coast, it became part of the Attic empire in

the 5th c. As its power waned, the fame of the sanctuary outside its walls grew,

culminating in the Hellenistic and early Imperial ages. Under the patronage of

the royal Macedonian house and the Diadochs, the venerable sanctuary was embellished

with splendid buildings that remained in use until the cult ceased in the late

4th c. A.D. In the 6th c. it was destroyed by an earthquake. But small Christian

churches dot the island and, like the 10th c. fortification built in the sanctuary

of spoils from its destroyed buildings, attest its continuing habitation. The

Great Gods of the Samothracian mysteries included a central divinity of pre-Greek

origin, a Great Mother (called Axieros in the native tongue, Demeter in Greek),

her spouse (Kadmilos, Hermes), and attendant demons (the Kabeiroi, Dioskouroi)

as well as the Greek Hades and Persephone (locally known as Axiokersos and Axiokersa).

Their nocturnal rites were available to men and women, freemen and slaves, unlike

the related rites at Eleusis. Initiation took place in two degrees, the myesis

and the epopteia, the latter not required but, if taken, preceded by an obligatory

rite of confession. It was not restricted to the annual festival but obtainable

at any time.

The Great Gods were special patrons of those at sea. Through their

mysteries the initiate gained protection, moral improvement, and probably the

hope of immortality. Although the initiation halls were accessible only to initiates,

the sanctuary was otherwise open to all visitors.

It lies to the W of the ancient city, is framed by two streams at

its E and W, and cut at its center by a third. The earliest monument, a rock altar

to the Great Mother, antedates the Greek settlers. In the 7th c. it was incorporated

in the N part of a double precinct beneath the later anaktoron, sacristy, and

Rotunda of Arsinoe, the S section receiving a bothros for libations to the Greeks'

underworld gods. Another rock altar outside the precinct and remnants of a small

sanctuary below the later temenos date from this period. In the 6th c. a rock

altar possibly dedicated to Hekate was added to this area and further to the S,

within and near the later temenos, additional altars and escharai were built.

In the debris from the sacrificial meals at one such place, quantities of fine

wheel-made local pottery of the 7th c. were found along with handmade ware. Within

the later Altar Court, a great rock altar arose and, adjacent to it, a rectangular

lesche, a Hall of Votive Gifts to judge by its contents, was constructed of small

limestone blocks and wooden ties. Its Doric colonnaded facade faced the central

river. The first halls of initiation were probably built at this time. The present

anaktoron, a rectangular building for the myesis, evidently succeeded a hall of

similar size, traces of which are preserved to its W. Built of stuccoed polygonal

masonry over the part of the earlier double precinct farther N, the anaktoron

contains two rooms, the larger entered through doors on its long W side; the smaller

and higher, at its rear, accessible only to initiates, who entered it through

internal doors. Installations in the larger chamber (a bothros in the SE corner,

a wooden circular platform, a grandstand along two walls) reflect the initiatory

rites. Spanned by wooden beams resting on piers engaged to its long walls, the

anaktoron is the earliest example of the Samothracian taste for clear spans of

exceptional size (10.58 m). A small building to its S served as a sacristy. Traces

of the first epopteion, an apsidal building for initiation into the higher degree

of the mysteries, are visible in the apse of its Hellenistic successor, the Hieron,

as are those of an intermediate early Classical epopteion.

About 340, an area long occupied by altars and escharai was enclosed

within a rectangular precinct preceded by a terrace. At its NE corner, where a

road descending from the E hill led down into the sanctuary, a propylon was built.

An Ionic porch with projecting wings preceded its door wall, its columns distinguished

by an ornamental necking, its coffered ceiling carved with male and female heads

shown in frontal, three-quarter, and profile views. Its entablature, the earliest

example of the later standard combination of dentils with a sculptured frieze,

also shows the first extensive use of the archaistic style for architectural sculpture:

a figural frieze probably alluding to the venerable ceremonies performed within

the precinct. The design of both the building and its sculptures may be attributed

to Skopas.

This first marble building in the sanctuary was followed by a series

of splendid structures largely built of Thasian marble. The Altar Court, dedicated

ca. 340-330 by Arrhidaios, half-brother and successor of Alexander the Great,

succeeded the rock altar beside the Hall of Votive Gifts. The Doric colonnade

of this unroofed enclosure also faced the river. Within it, steps now led to a

marble altar. The Doric Hieron was built ca. 325 to replace the early Classical

epopteion. Its rectangular cella lined with lateral benches ended in a raised

abaton, a segmental apse covered by a tentlike wooden roof. The painted stucco

walls of the cella imitated its outer drafted-margin masonry beneath a wooden

coffered ceiling and trussed roof (clear span 10.72 m). Candidates for the epopteia

entered the Hieron through its front door; epoptai, through lateral doors. A lustral

drain near the entrance, an eschara, and the curtained abaton were centers of

ritual action. The deep, hexastyle prostyle porch was not completed until 150-125

B.C. when it received a sculptured coffered ceiling (centaurs, grapes) and the

building was adorned with pedimental sculptures and akroteria at both ends (front:

the Nurturing of Aetion; rear: relief busts of the Samothracian Gods; central:

floral akroteria; lateral: Nikai pouring libations). Damaged by an earthquake,

the rear akroteria were replaced in the early Imperial age. Toward A.D. 200, the

cella was remodeled when the Kriobolia and Taurobolia of the Great Mother were

added to the cult, necessitating enlargement of the main door and the introduction

of parapets before the benches. A pair of monumental torches stood at the corners

of the porch. A third torch flanked by a pair of stepping stones outside the cella

was the scene of the rite of confession preliminary to the epopteia.

Between 323 and 316, another hexastyle prostyle Done building was

erected over a Classical predecessor. Standing on the E hill, near the entrance

to the sanctuary, it was a gift of Philip Arrhidaios and Alexander IV. A shallow

Ionic porch abutting its rear wall overlooked the paved stepped ramp leading downhill

toward the Temenos. Its coffered ceiling was carved with floral motifs. In front

of the Doric facade stood an altar or monument. Below it lay a paved circular

area ca. 9 m in diameter. Encircled by rows of concentric steps of Classical date,

it may have had a central altar. Statues, monuments, and inscriptions framed this

area.

Between 289 and 281, the rotunda dedicated to the Great Gods by Arsinoe

rose over the old double precinct. Built for sacrificial purposes, it is ca. 20

m in diameter. Its plain marble drum was surmounted by a gallery, Doric on the

exterior, Corinthian on the interior, decorated with a parapet of sculptured bucrania

and paterai. Its conical roof crowned by a hollow finial may have been screened

on the interior by a wooden dome. Inside and at its periphery, there were altars

and shafts for libation. Construction of the rotunda led to removal of the sacristy,

which was now rebuilt against the anaktoron. Marble benches, lamps, and stelai

recording initiations inserted into its stuccoed polygonal walls attest its use.

Like other buildings in the sanctuary, it shows traces of Late Roman repair.

The Propylon of Ptolemy II erected between 285 and 281 gave access

to the sanctuary from the city. On both sides of its door wall there was a deep

hexastyle porch, Ionic on the outer city side, Corinthian on the inner sanctuary

side. This is the first documented use of the latter order as an exterior structural

member in Greek architecture. Bucrania alternate with rosettes on its sculptured

frieze. A marble forecourt preceded the Ionic porch; another may have lain before

the ramp leading down to the circular area on the E hill. The river bounding the

sanctuary on the E originally passed through the cut-stone barrel vault running

diagonally through the propylon's foundation. In the wake of an earthquake, probably

in the 2d c. A.D., it assumed its present course to the W of the building. A wooden

bridge now led across the river from the propylon to the higher barren area above

the buried Classical circular structure. Neither it nor the royal dedication on

the hill was replaced.

A stuccoed limestone Doric stoa built on the W hill overlooking the

sanctuary in the 3d c. provided shelter for visitors. Two-aisled and ca. 106 m

long, its inner order was Ionic. Its painted stuccoed walls were incised with

lists of initiates. Probably its rear wall was pierced by doors giving access

to a broad area where a two-roomed structure was built against the stoa in the

4th c. A.D. A line of monuments stood to the E of the columnar facade above the

terraced hillside where structures, probably for ritual dining, were successively

built from the 4th c. B.C. to Late Roman times. A Hellenistic niche of pseudo-Mycenaean

style may have represented the tomb of a Samothracian hero. to the S, the outline

of the theater built ca. 200 B.C. appears. The white limestone and red porphyry

seats of the cavea faced the Altar Court which served as its skene. Above the

theater stood the Victory of Samothrace, part of a ship-fountain of the same period

framed by an enclosure of retaining walls. The rectangular precinct is divided

into an upper basin in which the prow of the vessel stood and a lower reflecting

basin from which natural boulders emerge and water was drawn.

North of the stoa, the W hill is largely occupied by a 10th c. Byzantine

fortification built of spoils from the sanctuary. Beneath it lie the foundations

of a large unfinished building of the early Hellenistic age; to its W a row of

three treasury-like late Hellenistic buildings once stood; to its E, a marble

building with an Ionic porch that led into the central of three rooms. Dedicated

by a Milesian lady in the 3d c., it, like other structures on the W hill, is still

under investigation.

Beyond the S limits of the sanctuary lies the S Necropolis, the most

extensive of the several burial grounds hitherto explored. Its tombs range from

the archaic period to the 2d c. A.D. and reveal the use of both cremation and

inhumation. The rich finds from the necropolis including ceramics, terracottas,

glass, jewelry, and other objects are exhibited in the Museum at the entrance

to the site.

Finds made since 1938 as well as the restored entablatures of several

buildings may be seen in the five galleries and courtyard of this museum. Objects

found by earlier expeditions, especially sculpture and architectural members,

were taken to the Louvre, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the Archaeological

Museums of Istanbul and the Archaeological Seminar of the Charles University,

Prague.

P. W. Lehmann, ed.

This text is from: The Princeton encyclopedia of classical sites,

Princeton University Press 1976. Cited Oct 2002 from

Perseus Project URL below, which contains bibliography & interesting hyperlinks.

(Samothraike), Samothraca, and Samothracia (Samothraikia). A small island in the north of the Aegaean Sea, opposite the mouth of the Hebrus in Thrace. It was the chief seat of the mysterious worship of the Cabiri. The political history of Samothrace is of little importance. The Samothracians fought on the side of Xerxes at the battle of Salamis; and at this time they possessed on the Thracian mainland a few places, such as Sale, Serrhion, Mesambria, and Tempyra. In the time of the Macedonian kings, Samothrace appears to have been regarded as a kind of asylum, and Perseus accordingly fled thither after his defeat by the Romans at the battle of Pydna.

This text is cited Oct 2002 from The Perseus Project URL below, which contains interesting hyperlinks

Samothraki, the Greek island where you can bathe under the shade of the sycamore trees

Temple dedicated to the Kabeiroi, the Great Gods of Samothrace.

Samothrace [2 Coins]-Perseus Coin Catalog

12/10/2001

22/4/2002

Receive our daily Newsletter with all the latest updates on the Greek Travel industry.

Subscribe now!